This number of The Mudsill will astonish and delight you. Our content in this issue tests the limits of the newsletter form: three captivating 2,000-word-plus essays and a pair of brilliant photographs mean that you will have to click the “more” button to see the full email. Worth it.

In Context, librarian and professor Keith Murchowski explains the fraught history behind the Wagner-Rogers child refugee bill, designed to provide a refuge to Jewish children and other persecuted religious minorities fleeing fascism in Europe. His essay, “‘Our Citizens, Our Country First,’” is sobering reading in this moment of resurgent nativism.

In Comment, scholar and activist Andrew Joseph Pegoda challenges our assumptions about disabled bodies in “Cripnormativity: How We Think (and Don’t Think) About Disability.”

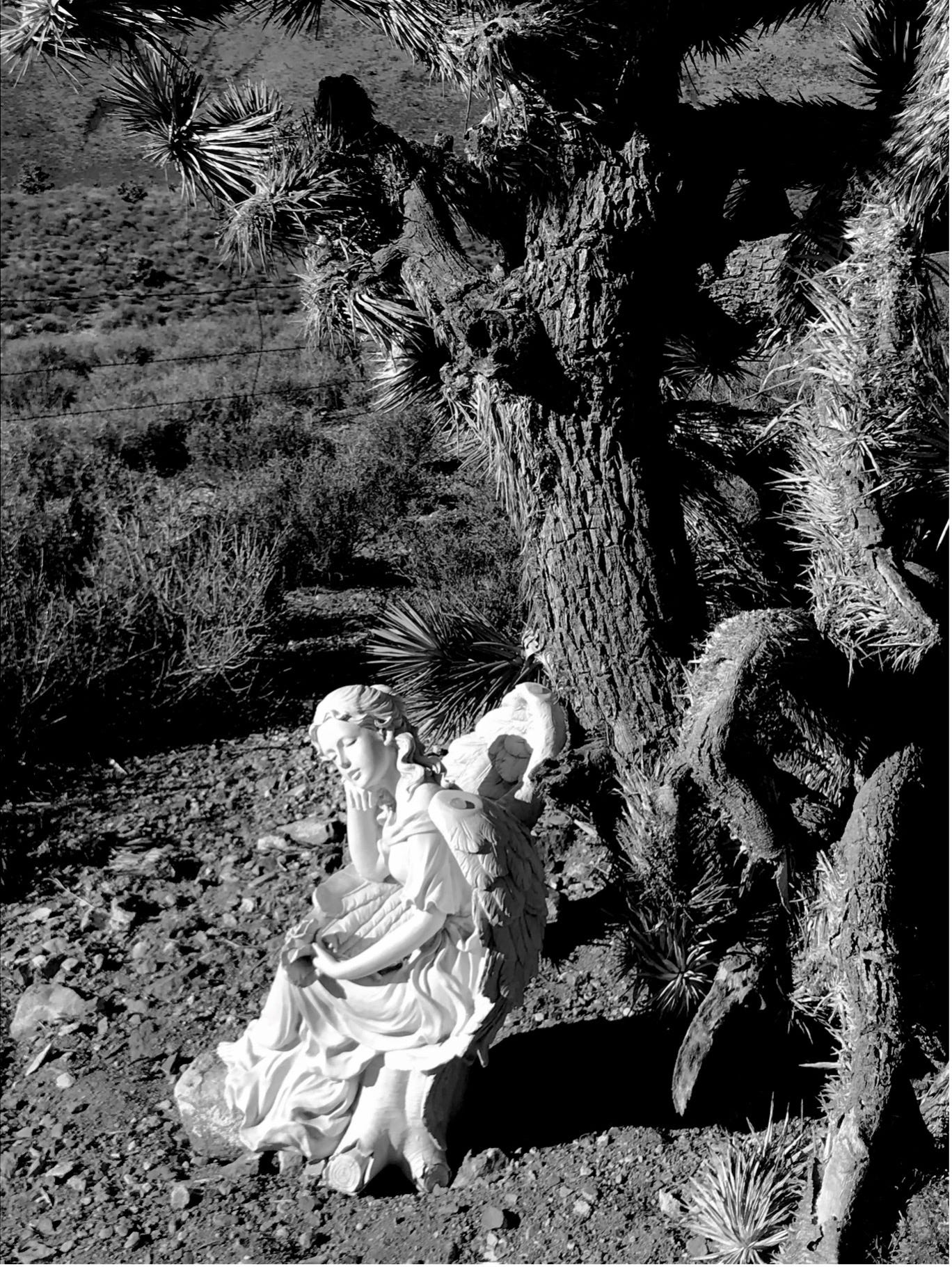

In Craft, historian and artist Doris Morgan Rueda brings us two stunning digital photographs offering a glimpse of life—or its traces—in the desert southwest. “The Angel of Caliente” and “Super Heroes in a Vegas Alley” were both created in 2020. The latter photograph is our cover image for this issue.

In Critique, we close out this number with an essay by poet and scholar Rebecca Raphael. “Captain von Trapp in the Age of Trump” reflects on the unforgettable performance of Christopher Plummer as Captain von Trapp, ripper of Nazi flags, and considers how that portrayal squares with both the history of the von Trapp family and with our own response to tyrannies and temptations alike.

Please share these important works with your friends.

“Our Citizens, Our Country First”

by Keith Muchowski

On the evening of Monday March 27, 1933 former New York governor Alfred E. Smith took the podium at New York City’s Madison Square Garden, then located on Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets, and spoke against rising intolerance in the Germany of newly-appointed Chancellor Adolf Hitler.

Religious bigotry was something with which Al Smith was familiar; he had been the Democratic Party’s 1928 presidential nominee and seen his candidacy derailed in part by anti-Catholic hatred, some of it manufactured quite openly and publicly by the renascent Ku Klux Klan whose membership had grown to as many as four million, North and South, by the mid-1920s.

Now twenty thousand packed the Garden to hear Smith and other civic, labor, and religious leaders denounce Hitler and Nazism. Tens of thousands more overflowed the arena as far north as Columbus Circle and listened over loudspeakers. The Madison Square Garden event was part of a nationwide initiative organized under the auspices of the American Jewish Congress, whose leaders had gathered at the Commodore Hotel on March 12 to plan a national response to events in Germany. The meeting date was not accidental: the 12th was Purim, the annual commemoration marking the ancient Jews’ deliverance from their Persian tormentor Haman in the fourth century B.C.E.

A modern tormentor, Hitler, had taken office on January 30 and quickly showed his intentions, consolidating dictatorial power after the Reichstag fire of February 27 and opening Germany’s first concentration camp, in Dachau, to house political prisoners on March 22. Other world leaders were coming to the fore at the same moment. Franklin Delano Roosevelt entered the White House on March 4 and in his First Hundred Days commenced an expansive domestic agenda to combat the depression causing so much political and economic strife. One of Roosevelt’s allies in Congress was Senator Robert F. Wagner, a Democrat from FDR’s home state of New York. Washington in the early days of the Roosevelt Administration was a busy place but Wagner briefly put aside the Congress’s legislative agenda that late March and arrived from the nation’s capital to speak and bear witness at the anti-Hitler rally in the Garden.

The concern was justified; as feared, Europe descended further into populism and authoritarianism in the coming years. What began as irresponsible rhetoric, street brawling, and book burning gave way to the Nuremberg Race Laws, the building of additional concentration camps, the 1938 annexation of Austria and violence of Kristallnacht, and increasing pressure and restriction on the civic and economic life of Jews and other undesirables into 1939. Meanwhile the Great Depression continued and Americans focused primarily on internal affairs. For Robert F. Wagner that meant the New Deal and related measures. In the mid-1930s Senator Wagner helped craft such legislation as the Social Security Act and the National Labor Relations Act that guaranteed workers the right to organize and bargain collectively.

As more of Europe fell under Hitler’s sway, many citizens in Austria, Germany, and elsewhere tried to emigrate. That was easier said than done because of the strict immigration laws passed in the United States in the wake of the influenza pandemic and Great War. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 set immigration percentages based on country of national origin for those who wished to relocate to America. Three years later the Johnson–Reed Act tightened those already stringent quotas and also created the visa system through which prospective candidates applied at U.S. embassies or consular offices in their home country to have their case assessed. Navigating this byzantine process was intentionally difficult and naturally curtailed immigration—as it was designed to. The number of Europeans coming to America fell precipitously throughout the Roaring Twenties. There were already strict immigration laws targeted against Asians.

Many Americans were concerned about events across the Atlantic, but isolationist sentiment remained strong and few wanted the United States to entangle itself in Europe’s affairs. What is more, because so many Americans were still overburdened and struggling with the effects of the Dust Bowl, Stock Market Crash, and unemployment during the Great Depression there was little inclination to relax the allotment numbers that had been in place now for more than a decade. When Henry Luce’s Fortune magazine asked Americans the question “What is your attitude towards allowing German, Austrian and other political refugees to come into the United States?” for its July 1938 issue, 67.4% of the responders selected as their answer “With conditions as they are, we should try to keep them out.” Less than 5% responded that the country should encourage the arrival of refugees if it meant raising quotas.

It was thus an uphill battle when Senator Wagner introduced Joint Resolution 64 onto the Senate floor on February 9, 1939. This bill, if passed, would grant visas to 10,000 German children under the age of fourteen in 1939 and another 10,000 again in 1940. These 20,000 children “of every race and creed” would be in addition to the 25,937 persons allowed into the United States annually from Germany in the 1930s under the quotas established by the 1924 Johnson–Reed Act. This quota limit was hardly if ever met because so few in Germany could meet the strict standards established by the visa system. There were less than 18,000 arrivals in 1938, and that was a jump from the 11,127 admitted the year before. In 1936, the year of the Berlin Olympics, just 6,073 Germans escaped Nazi Germany to the United States; the other nearly 20,000 visas allotted for that year went unused.

For Wagner the immigration bill was partly personal. Robert Ferdinand Wagner himself had been born in German city of Nastätten in June 1877. After his family came to America young Bob had difficulty making himself understood to his English-speaking classmates at the public school he attended on Manhattan’s East 110th Street. A gifted student, he learned quickly and eventually attended City College of New York and then NYU Law School before entering public service in the early 1900s. Wagner rose with the help of the Tammany machine and easily negotiated his way through cutthroat Empire State politics in Albany as a state legislator. Wagner and Al Smith, with whom he would share that Madison Square Garden stage decades later railing against authoritarianism, came to prominence investigating the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911. Other allies in the ethnic stew of New York politics included Fiorello H. La Guardia, Jimmy Walker, Herbert H. Lehman, and of course Franklin D. Roosevelt. Wagner was elected to the United States Senate in 1926.

When Wagner entered his bill onto the Senate floor in February 1939, Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers (R-Massachusetts) introduced a similar measure into the House. Congresswoman Rogers was not born in Germany, but in Saco, Maine in March 1881. Edith Nourse married John Jacob Rogers in 1907 and the two settled in Lowell, Massachusetts, where Mr. Rogers practiced law and in 1913 entered the U.S. House of Representative representing the Bay State’s Fifth District. Rogers and his wife were both active in the effort during the Great War. After that conflict the two settled into Washington life and worked on veterans affairs and other issues.

When Congressman Rogers died in 1925 his wife ran for his seat and won, becoming the first congresswoman ever from New England. Now nearly a decade later there she still was, in Washington representing the people of the Massachusetts Fifth. What the American public came to know as the Wagner-Rogers Bill would be debated furiously that winter and into the summer of 1939. There must have been an added sense of urgency when on February 20, less than two weeks after the Wagner-Rogers proposal reached the House and Senate, the German-American Bund held their own Madison Square Garden rally. These were just some of the estimated nearly 200,000 American supporters of the German Führer. Over 1,700 policemen, many of them mounted, ensured the peace at the packed Garden. Outside however fights between Hitler’s American supporters and those opposed to them broke out on the sidewalks.

Religious leaders of many faiths supported the Wagner-Rogers Bill. Various political figures from across the spectrum did as well. Former president Herbert Hoover, who defeated Al Smith in 1928 but lost his reelection to Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, expressed his support in a telegram read aloud to the Senate Immigration Committee on April 22. That same week Alfred M. Landon, the 1936 Republican Party presidential candidate defeated by FDR, announced his support via a letter to the executive director of the Non-Sectarian Committee for German Refugee Children. Landon’s missive, like Hoover’s, was read aloud in Congress. The bill received support from what might seem surprising sources given the economic times: the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The leaders of these groups did not see the arrival of 20,000 political refugees under the age of fourteen as a threat to American jobs and industry.

Other groups were equally opposed. Among these included the American Legion, the New York Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS), and the Daughters of the American Revolution. That same April the DAR declined to allow Marian Anderson to perform at Constitutional Hall. Instead the African-American contralto sang at a hastily arranged concert before 75,000 from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday, April 9. Opposition from the American Legion and other veteran organization must have hurt Congresswoman Rogers particularly hard given all she had done in Europe with the Red Cross during the Great War and for veterans affairs afterward.

Not wanting to get ahead of the American people, President Roosevelt himself was a somewhat reluctant supporter of refugees and their plight. He had half-heartedly lent support to a conference in the French spa town Evian-les-Bainsheld July 6–15, 1938 and attended by representatives of over thirty nations and three dozens nongovernmental organizations. Little happened at the Evian Conference though from it did come the establishment of the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees (ICR). By 1939 events in Europe were moving quickly and the plight of refugees was very much in the news. Starting in late December 1938 the Kindertransport began relocating children from Nazi-threatened Europe to Great Britain; thousands of youths arrived over the next two years. In summer 1939 the St. Louis carried some 900 souls to various Atlantic ports seeking refuge; most were returned to Europe.

Besides Wagner and Rogers a third major player was North Carolina senator Robert Rice Reynolds. Reynolds’s inconsistent support for the Administration and its policies reflected the tenuous nature of the Roosevelt coalition of northeastern ethnics and southern Dixiecrats. “Buncombe Bob” had done much to secure New Deal funds for the Tar Heel State and supported a large number of President Roosevelt’s domestic initiatives but remained a staunch isolationist and would prove unmovable on issues of neutrality and refugeeism.

On January 31, 1939, just days before his legislative colleague Robert F. Wagner introduced his child refugee bill, Senator Reynolds founded the Vindicators Association, Inc., an isolationist organization with offices within view of the Capitol Building. The Vindicators eventually grew to approximately 50,000 members under the slogan “Our Citizens, Our Country First.” Starting in April 1939 the organization published its own vehicle TheAmericanVindicator; over three dozens issues would roll off the presses before TheAmericanVindicator ceased production in December 1942. Readers were offered swag which included a red, white, and blue feather; a lapel pin; and a Gadsden flag, the banner dating back to the Revolutionary War era with a coiled rattlesnake imposed on a yellow field above the words “Don’t Tread on Me.” Reynolds and the Vindicators had a five point mission:

1. Keep America out of war.

2. Register and fingerprint all aliens.

3. Stop all immigration for the next ten years.

4. Banish all foreign isms.

5. Deport all alien criminals and undesirables.

The affable Reynolds vehemently denied holding authoritarian tendencies but his associates included George E. Deatherage, chief of the reconstituted Knights of the White Camellia, and Father Charles E. Coughlin, the radio priest who from his pulpit at Royal Oak, Michigan’s Shrine of the Little Flower reached forty million listeners each week railing against Roosevelt, the New Deal, the British, the Jews, “international money-changers,” immigrants, and others.

In this milieu then it is not surprising that the Wagner-Rogers Bill allowing the emigration of up to 20,000 German children to come to America did not pass. It never even came up for a congressional vote. Senator Wagner withdrew the bill in July when it became apparent that it would not receive the requisite votes. The following month Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and on September 1, 1939 war finally came to Europe and the continent descended into chaos. The United States technically remained neutral for almost 2 1/2 years, though President Roosevelt helped the Allied powers to the extent he could through such measures as the Lend-Lease Act. On December 7, 1941 the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

Keith Muchowski is a librarian and professor at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) in Brooklyn.

Cripnormativity:

How We Think (and Don’t Think) About Disability

by Andrew Joseph Pegoda

Conversations around and representations of disability and illness typically center around what I name cripnormativity. In brief, cripnormativity is what society and its structures – for instance the medical gaze – see as acceptable, normal forms of disability.

“Cripnormativity” parallels well-established concepts such as chrononormativity, cisgendernormativity, heteronormativity, and homonormativity. For example, homonormativity, in part, describes acceptable ways of being queer and how society expects queer people to exist. In the United States, homonormative images typically include able-bodied, conventionally attractive white cisgender men who are interested in culture but also want to get married and have children. Basically, the stereotype of a gay person.

The aforementioned systems of normativity each explicitly embody systems of privilege and the corresponding contexts, Histories, institutions, performativities, and texts that normalize and perpetuate said normativity. These systems of normativity also all compel toxic neoliberalvalues, including assimilation, conformity, invisibility, exceptionality, predictability, and responsibility.

Importantly, all of these systems are socially constructed, even disability. For instance, some people can’t drive for medical reasons. In Houston, Texas, that would be considered a disability. Driving is effectively compulsory in the Houston area, an area spanning 10,000 square miles and without widespread public transportation. In New York City, where very few drive and where public transportation is the norm, such a person would not even be noticed as a “non-driver,” and therefore would be less “disabled.”

Disabled and ill bodies only ever receive conditional acceptance to the extent that their attitudes, behaviors, and conditions are “cripnormative.” Cripnormativity rewards what is deemed acceptable and thought “cool,” what is not-too-disruptive and not-too-expensive, and who is a “victim” of biology or of a tragic accident but who also takes responsibility.

I’m reminded of an evening when I was reviewing an agenda from the Alvin Community College Board of Regents. One of the items was “dismissal of a tenured professor.” Digging into the agendas and meeting minutes, I learned that this was a professor fighting cancer for longer than what had been initially expected. This professor had exhausted sick leave options. And so, in perfect cripnormative mores, this professor was fired, a termination that would also terminate life-saving health insurance. Disabled and ill individuals can be accepted but only with many buts and many arbitrary time limits.

Cripnormativity insists that there are “proper” and “improper” ways for the crip to exist. Cripnormativity even creates intraminority stress and horizontal hostility among the disabled, whereby disabled people judge other disabled individuals for not “behaving” in the correct way” or for “worsening” their own condition through “poor” choices of what they put in their bodies when in reality they are likely engaged in harm reduction.

Take Greg Abbott, the much loathed, long-time Texas attorney and governor. He has been confined to a wheelchair for almost forty years. He holds far-right political and far-right religious views. His ideologies, and that of other Republicans, actively hurt opportunities for the disabled. Abbott is cripnormative inasmuch as his ideologies make him acceptable to the status quo, he serves as an textbook case of “overcoming the odds,” and he refuses to adopt any kind of crip-positive perspective toward others. He’s disabled without being “disabled.”

People might be afforded the privilege of cripnormativity if they have a condition that is generally heard of, perhaps depression or Muscular dystrophy. Further, society often ignores invisible disabilities – such as depression – not always because such are forgotten but because such are rewarded under cripnormativity. Those who can “manage” or hide chronic pain from migraines or from incisions are also awarded a kind of cripnormativity.

The appearance of assimilation and normalcy is what matters.

Additionally, those who are racialized as white, who are sexed as male, who are gendered as cisgender men, or who are famous and who have non-normative bodies might also fall into frameworks of cripnormativity and its privileges, take Stephen Hawking. Like all types of privilege and oppression, cripnormativity depends on other axes, including class, gender, race.

The following personal examples help further illustrate cripnormativity.

In March 2020, I was at Hanger Clinic in Houston, Texas, to be fitted for my new leg brace – a prosthetic device for my right leg that extends from my toes to my knee because of Neurofibromatosis. I’ve had to wear such braces for over twenty years. At one point, the clinician commented, “You’re [in contrast to other patients here] probably someone who doesn’t even consider themselves disabled.” It was meant as a compliment. To say this “compliment” left me baffled and upset is an understatement. As a survivor of many surgeries and on-going medical issues and as a researcher, “disabled” and “chronically ill” are only two of my many identifiers I embrace with pride.

And yet, I am an-almost perfect example of cripnormativity and have been privileged.

I was born ill and disabled. I'm a 6’6”, masculine-presenting, white individual with excellent health insurance. I do not need disability income or food stamps for survival, as many disabled people do. I have always had plenty to eat and always had safe water. I have never used tobacco or any illegal substance that others could say contributed to my problems. I don’t drink alcohol. People often say that I have “overcome” and that I am “inspiring” due to my academic success and career as a professor.

Through sheer bodily experience and from negative reactions in the past, I’m generally very good at hiding chronic pain. For many, many years now, I have always and only worn long jeans or pants – never shorts – because if my legs are visible, strangers demand answers. Currently, with some exceptions applicable to those ready to scrutinize as I have an ever-growing number of small tumors called neurofibromas on my arms and face, I am – therefore – not visibly disabled.

I am “invisible” as a disabled person insomuch as my needs are minimal, though through no choice of my own. Although, I do often depend on disabled parking spots. We are all dependent on others, but a manifestation of cripnormativity – except for the very most famous or the wealthiest or the oldest, the exceptional – is being able to bathe, dress, and eat without assistance.

Our culture has trained me to assimilate, to make my very visible physical differences invisible, and thus, further forced cripnormativity onto me.

Due to institutional harassment in public school, I kept all of my learning disabilities and medical problems to myself throughout much of college for fear of what disclosure would lead to. Just as society teaches every one to be cisgender and heterosexual in what can be called compulsory heterosexuality as named by Adrienne Rich, compulsory able-bodiedness as named by Dr. Robert McRuer demands cripnormativity: Rather than a reality of life for everyone, disability is seen as a different kind of existence and is only talked about when permitted by other tenets of cripnormativity. In other words, no one is as able-bodied as they think, and being disabled or ill is not a completely separate experience, but everyone is expected to be as “normal” as possible.

There are, however, limits to my forced “cripnormativity” – unlike breast cancer or Parkinson’s disease, for example, Neurofibromatosis is highly unpredictable, is highly variable, is hardly known, and has miniscule popular funding. Hollywood movies have characters facing various cancers but never Neurofibromatosis, even though it is the most common genetic disorder affecting approximately 1 in 2,500-3,000. If PBS or NPR hosted donation drives for Neurofibromatosis, it could gradually enter cripnormativity.

Cripnormativity controls how we see and think about disability.

In addition to forcing all to “fake wellness,” cripnormativity creates “crip deserts” – borrowing from “food desert” and “education desert” phraseology.

Game shows like Jeopardy! and Wheel of Fortuneare prime examples of the crip desert. Contestants never appear in wheelchairs, never have missing arms or legs or fingers, never have visible scars from surgeries or fires, never have assistance pushing buttons or spinning wheels, and never communicate with speaking disabilities. In 2019, Wheel of Fortune – a show that premiered in 1975 – had what was called its first Deaf contestant in a “Best Friends Week” but did not accept the Deaf player’s answers because the game requires players to communicate in “correct” spoken American English. (Wheel of Fortune also does not invite those with strong accents to play its game.) Puzzles on Wheel of Fortune never even include indications that disabled and ill bodies exist. “Cancer Survivor” will never be a puzzle under the Person category.

Because disability is part of the human experience and all bodies operate differently, we know that players often have some forms of some disabilities, but in a perfect manifestation of cripnormativity, these are completely erased.

The therapist’s office is another “crip desert.”

There are simply not enough professionals devoted to mental health. In the entire state of Mississippi, there are 596 therapists for almost 3 million. In Houston, there are only 1,921 therapists for a population of over 2 million, of these most do not take health insurance through no fault of their own (insurance reimbursements are extremely low, for instance) – 694 take BlueCross BlueShield, 579 Cigna, 482 United Health Care.

(All data according to Psychology Today’s registries and current as of December 2020.)

For those who do not have insurance or who cannot find a mental health professional who accepts insurance, sessions typically run from $100-$400. “Self-pay” immediately eliminates many of those who need help the quickest.

Seeing a therapist is increasingly accepted in our society, although more so for white people, and positive representations exist in a growing number of movies and television shows. Thus, seeing – rather being able to see – a therapist provides access to the privilege of cripnormativity, a luxury often available only to those with extra money and extra time. Money can even effectively buy some cripnormativity.

I often hear from students who really want to see a therapist but cannot. Some scholarships or charity clinics are available, but these often force applicants to “perform their poverty” and to “perform their crip-ness.” Potential patients have to prove they are really desperate, when the powers at be – namely the Imperialist White Supremacist Capitalist (Heteronormative Ableist Theistic) Patriarchy as named by Dr. bell hooks– know that we are all trained to resist such disclosure and voluntarily shedding privilege. As stated by Dr. Susan Wendell in The Rejected Body, seeking mental health workers, especially with a psychiatrist, can even be dangerous as they can order that you be institutionalized, completing taking away any opportunities to be cripnormative, to pass as able-bodied.

Educational institutions serve as another location of the crip desert and of the cripnormative.

Schools, including colleges, habitually discriminate against disabled students and employees. These houses of learning also create hostile environments: Crip bodies are often seen as less capable.

Job ads at colleges and universities, in what are clear legal violations, frequently require that professors be able to walk, to see, to hear, and to lift heavy boxes.

A conversation I had with a mentor back in 2007 when I was an undergraduate applying to graduate programs comes to mind. I was sharing my own disabilities with this mentor and asking if I should share those with these programs. She said, “No. Grad school professors won’t follow any accommodations anyway.” In these cases, there is not even toleration for the cripnormative in institutions of higher education. And, given the realities, gave sound advice.

I remember a non-traditional, blind student I had, too. This student certainly had some behavioral issues, such as using inappropriate language in class and talking over me and over other students but was a valued member of the class community. Other students enjoyed their contributions. The Disability Office, however, knew this older student could be, as they put it, disruptive, and this office regularly demanded details about the student’s classroom behavior, even going so far as scheduling a meeting with the Chief Student Affairs Officer that I and others were to attend. This student and I got along fine, and I was never bothered, but they were not the “quiet,” “obedient,” “traditional” cripnormative student expected. #RealCollege students are different.

Cripnormative students in K-12 are able to have the appearance of coping with few or no breaks, with short lunch periods, and with chronic dehydration. Throughout public school we were prohibited from having a bottle of water. The school nurse ensured children would come only if absolutely necessary by yelling regularly. I also recall the teachers who insisted on using a pink whiteboard marker that I couldn’t see, who refused to grant homework extensions after a major surgery, and who said I didn’t really have migraines. Disabled people who can withstand these oppressive goals might be granted cripnormativity.

Cripnormativity is also concerned with maintaining structures as they are and only making some accommodations when needed, not legitimizing crip time and not aiming toward “Universal Design,” where curriculums and classrooms are designed with adaptability and with flexibility and are immediately ready for anyone regardless of how their body and mind operate. Accommodations cripnormative ill and disabled people need for equitable learning are familiar to the disability office, are free or low-cost, are likely to cause no or minimal “disruption,” and are not likely to require additional work for faculty/staff on the rare occasions that accommodations are actually followed.

My hope is that cripnormativity will help start new conversations about the specific ways in which disability is and is not accepted and about the forces operating at or just below the surface. Some who have disabilities are welcomed in society and might thrive. Others are not. Recognizing and challenging the cripnormative helps provide answers and helps chart future opportunities for the expansion of human rights.

Andrew Joseph Pegoda (@AJP_PhD) holds a Ph.D. in History and teaches women’s, gender, and sexuality studies; religious studies; and English at the University of Houston. Previous articles can be found in The Conversation, History News Network, Inside Higher Ed, Time, and The Washington Post, among others.

The Angel of Caliente (2020)

by Doris Morgan Rueda

Super Heroes in a Vegas Alley (2020)

by Doris Morgan Rueda

Doris Morgan Rueda is a historian and artist currently living in Las Vegas, Nevada working on her doctorates in legal history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Her doctoral work focuses on the development of juvenile justice system along the American Southwest with an interest in race, youth, and identity. As an artist, she focuses on working in exploring the lines between reality and the absurd through a variety of mediums from digital art to acrylic painting.

Captain von Trapp in the Age of Trump

by Rebecca Raphael

When Christopher Plummer died on February 5, tributes emphasized that best-known role for which Plummer always expressed ambivalence (at best): Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His passing shortly after the Trump administration ended highlights an image that has been with American social media and internet culture for five years: the Captain as anti-Nazi. On February 5, essayist Rebecca Solnit posted to Facebook this meme by Monshin Christian Piñon (1): in the folk festival scene, the von Trapp family performs “So Long, Farewell.” Across the image, Piñon added in red letters “Antifa.” Solnit commented, “Rest in Peace, Christopher Plummer. Antifa hero since 1965. Adding Susan’s do re mi (anti) fa joke here.” Solnit commits a small anachronism: Captain von Trapp has only been an antifa hero in American internet culture since 2016. The Trump-era antifascist reading of the Captain, expressed in memes and gifs, has been the creation of a specific American cohort: liberal to leftist, anti-trump to antifascist, Gen X and younger people who grew up viewing The Sound of Music. Plummer’s death prompted me to this question: What is this antifa Captain doing with his source material?

The Meme Captain

The most frequent Captain meme appears in gif form: he rips apart a Nazi flag that someone hung on his house, in his absence, without his consent. A curl of distain on Plummer’s mouth accompanies the visceral gesture. If we use Twitter as a barometer, interest in this meme peeps over the horizon of 2016. In November 2016, just after the election and when legacy networks usually air The Sound of Music, Mother Jones editor Clara Jeffrey suggested that D.C. needed a Captain von Trapp review. Search “Sound of Music gifs” on gifer-dot-com, and the first cinematographic image you find is the flag-tearing. “Sound of Mucus” or no, if you search “Christopher Plummer gifs,” this is what you get, followed by a forest of Captain images. (Sorry, Chris.)

The flag-tearing gif is the crest of a larger wave of SOM-anti-trumpist internet culture. Shortly after American Nazis terrorized Charlottesville, McSweeney’s published “President Trump’s Statement Following the Events in The Sound of Music,” by Kathryn Funkhauser. The fictive trumpian voice berates von Trapp as a leftist who tore up “a high-quality flag.” One anonymous memer photo-shopped the Confederate battle flag into the usual gif, making overt the parallelism with our own conflicts. Gabrielle Hoyt wrote in 2019 that “It is precisely the un-Jewishness of von Trapp that keeps me coming back to this gif. He has no vested interest in opposing the Nazis… and yet he considers it a moral imperative to do so.” Hence the meme’s function as an internet reply to anti-semitism and other bigotries. In the late Teens in the U.S., this gif is the film’s meaning.

The Piñon meme links a different image of the Captain – and the whole family – to antifascism. Surely, too, the connection is the motif of farewell, to Plummer. And perhaps, by polyvalent meaning, to Trump: this is where the von Trapps say farewell to Nazi rule and become refugees. In these memes and gifs, the generations that have come up since the United States’ first year as a full democracy express their understanding of this unavoidable film: if and when Nazism comes, reject it. Unequivocally.

The Film Captain

Is this what the film means? Throughout, Captain von Trapp is adamantly anti-Nazi – but why? The only motivation provided by the script is Austrian nationalism. The Captain’s first encounter with Nazism comes at 1:09, when the Captain shoos Heil-Hitlering Rolf away, and the Baroness and Max try to cool him down. Von Trapp refers to his Austrian identity here, later at the ball scene, and most poignantly at the festival performance just before their escape. In 2003, Robert von Dassanowsky argued that the film is an allegory of Ständestaat Austria, the period of late 1930s which combined the Hapsburg past, Catholicism, and Tyrolian rural culture into a non-democratic but nevertheless decidedly anti-Nazi politics. This article and Peter Levine’s 2012 post discussing it focus on the film’s semiotics (2). Both authors secure the film’s explanation for von Trapp’s anti-Nazism in its evocation of one version of 1930s Austrian identity. Personally, I think the Hapsburg signifiers are stronger than von Dassanowsky rates them. (3) After all, nothing in the movie signals that Austria doesn’t still have an Emperor, or even a Navy. Their account, though, more or less works for the script and for the characters and romantic matches as allegories.

However, something about the film Captain doesn’t seem to sit entirely in that box, especially on a post-Trump viewing. The excess is move evident in the first Georg-Rolf confrontation and the adult discussion that follows it. Plummer’s facial expressions, voicing, and gestures convey an explosive emotion that feels excessive for the script’s overt references. The script, too, slips its moorings by having the Captain so utterly, clearly, deeply anti-Nazi: he never wonders, for instance, if he should accept the commission for his family’s sake, or asks if his fidelity to a version of Austria that is merely 20 years old warrants this level of risk and sacrifice. These are odd issues to omit, even in deference to dominant love story. The film Captain is an admirably immovable object: he always knows what is coming, and he always knows what he will do about. This unwavering quality is perhaps exactly what we have needed through the past five years. Yet we should also know by now that these choices are not always clear to their makers.

The Historical Captain

Hollywood simplifies; what was the complex reality?

The von Trapp family has long demurred from the film’s portrayal of the Captain. He was, his adult children said, not an emotionally distant drill master but a loving and engaged father. Accounts of the differences between reality and the film are easy to find. The most salient here is that von Trapp married Maria Augusta Kutschera in 1927, and his elder children were young adults by the late 1930s. To understand why the Third Reich came calling at Villa Trapp, let’s turn first to the Captain’s naval record. He was a career navy man and, in World War I, a submarine commander. U-boats under his command sank thirteen ships, some with significant casualties. The man had a chest full of metals, far more than the two we see in the film’s wedding scene. In the 1930s, Georg von Trapp composed a memoir of his World War I deployments, in which he gave detailed accounts of his naval battles and some clutch tactical thinking. (4) Along the way, he expresses pride in the polyglot Austrian-Hungarian Empire, a somewhat veiled distain for Germany, and enormous grief at the disintegration of his country. As the war ends, he and another sailor view themselves as homeless, at home only in the navy (Von Trapp/Campbell, 179): “Where do I belong actually? Where am I really at home? Nowhere at all! Father: navy officer. . . . it’s in the navy that I am at home, or, if you will, at sea!” Then the Austrian-Hungarian Imperial Navy also came to an end.

Before the Nazis attempted to commission/conscript the Captain into Hitler’s navy, the family began to run afoul of a Nazifying social environment. They became guarded in how they talked at home, since at least one of the household staff was a Nazi. The children’s school summoned Maria several times because their daughter Lorli, a first-grader, refused to salute Hitler or sing the Nazi anthem. Soon they decided to keep their first-grade resister home. The von Trapps knew in 1938 that Jews and political dissidents were disappearing from their jobs and homes. They knew about concentration camps: the possibility of the Captain ending up in one, as a dissident, was a live concern. (5) Von Trapp was anti-Nazi years before the Anschluss. (6)

So what happened when Hitler’s government invited* (7) this adamant anti-Nazi who loved the navy and excelled at submarine warfare to command larger and more advanced submarines than existed in WWI? Maria recounted her husband’s reaction to what appears to have been the first order (122-123). Georg has a brief moment of excitement at the thought of larger, more advanced submarines than the ones he sailed in WWI. He also detected that the Nazis intended expansionist warfare. He worried whether his oath to the Emperor obligated him to a subsequent head, whom he found abhorrent, of a different state. Others had told him to fall in line, lest his children be threatened. He thinks about all of this. But he could not sink ships for Hitler: “I can’t run a submarine for the Nazis . . . It’s out – it’s absolutely out. . . .” To do so would violate his Catholic religious principles, his previous Hapsburg loyalties, and his most basic moral compass. Just no.

Shortly afterward, the family received other invitations* from Hitler’s government. Eldest son, Rupert, a recent medical school graduate, was offered a job that he knew opened because its previous Jewish holder had been disappeared (M. A. Trapp, 123). For that reason, and on religious and political grounds, he refused. Then the family was asked to sing for Hitler’s birthday. Georg held a family meeting about these invitations*. The Nazis were anti-Catholic, anti-Jewish, and anti-Austrian as the von Trapps understood Austria. One family member asked if would be possible to hold anti-Nazi principles while accepting such offers. After that question, Georg spoke:

“This will be the third time we say no to a distinguished offer on the part of the Nazis. Children,” and their father’s voice didn’t sound like his everyday one, “children, we have the choice now: do we want to keep the material goods we still have: this our home with the ancient furniture, our friends, and all the things we are fond of? – then we shall have to give up the spiritual goods: our faith and our honor. We can’t have both any more. . . .” (M. A. Trapp, 124-125.)

We can’t have both any more. Accepting Nazi offers* of position would betray his and his family’s fundamental moral commitments. So they went into exile and many years of poverty.

Georg von Trapp was no leftist, by the standards of his time or ours. He descended from Austrian aristocracy, married into wealth, and earned titles with his own naval service. In his memoir, he fleetingly expressed disdain for “Bolsheviks” and nationalists whom he saw as shredding the older order. His old loyalties did not die with the structures to which they were tied, even as he abhorred the Anschluss as an obliteration of Austria – what was left of it after 1918. He had no involvement with antifascist movements of his time. (7) His anti-Nazism was deeply grounded, and he knew exactly what that would mean.

Conclusion

Admit it: you want to know if the flag-ripping scene actually happened.

Not exactly. One day, a Nazi operative called at Villa Trapp because the house did not display the Third Reich flag. Georg said that he could not afford one. Calling this bluff, the operative left, returned later with a flag, and insisted that Georg display it. “You know,” said Georg, “I don’t like the color. It’s too loud. But if you want me to decorate my house, I have beautiful oriental rugs. I can hang one from every window.” (M. A. Trapp, 117) While this verbal middle-finger did no harm to a flag, the words were not private. Von Trapp said this to a Nazi operative’s face.

We Americans of the Trump era have, with these Captain memes, been hoping for this kind of courage. Internet culture has mined widely shared cultural currency – The Sound of Music, the storming of Normandy – to construct an anti-fascist American past out of things we (used to) agree on: that Nazism is evil and should be soundly rejected. Yet another WWII reference seems apropos of Georg von Trapp: the Martin Niemoller poem, “First they came for. . .” This, too, has been ubiquitous in social media. In the poem, “they” come for groups to abuse rights, to put people in camps, to exterminate them. We overlook the American crimes that of course of not listed in a German poem. Even so, Captain Georg von Trapp points out something else the poem omits: “they” might not come with overt intent to abuse and exterminate you. Sometimes “they” come with opportunity, they come for skills, they came for the proximity and complicity of the privileged. For the Captain, they came asking him to do what he was best at and enjoyed. And that warrior of a lost empire said no. We have been using his image also to say no. Absolutely not.

(1) Disclosure: I shared Solnit’s post of this meme. I shared other Captain memes too. I’m part of what I study here.

(2) I thank Martha Newman of UT-Austin for pointing me to these articles.

(3) For example, Von Dassanowsky reads the Captain’s medal in this scene as a Ständestaat signifier, but it is a fairly accurate replica of the Order of Maria Theresa medal, a military decoration of the Hapsburg Empire.

(4) Georg von Trapp, To the Last Salute: Memories of an Austrian U-Boat Commander. Translated by Elizabeth M. Campbell. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. The memoir was first published in German in 1935. Ms. Campbell, who is the granddaughter of Georg and Maria von Trapp, kindly answered some of my questions by email.

(5) Maria Augusta Trapp, The Story of the Trapp Family Singers (New York: William Morrow, 1949/2002). This section draws primarily from material in chapter 13.

(6) Eldest daughter Agathe von Trapp wrote in her 2003 memoir of an incident in 1933-34 when some young men approached the vacationing family. Her father was suspicious that they might be Nazis out recruiting. Memories Before and After The Sound of Music (New York: HarperCollins e-books, 2010).

(7) The asterisk indicates the vocal intonation of Plummer saying the word “requested” when the Captain informs Maria of the orders from Berlin (2:27).

(7) Personal communication with Elizabeth Campbell.